— Chapter Twenty-Five: The Great Red Dragon —

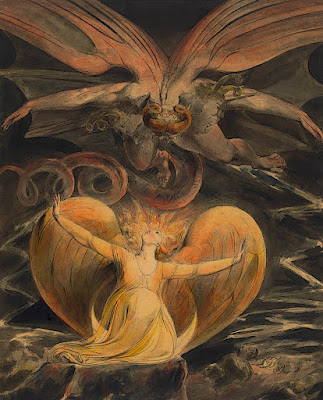

The Great Red Dragon and the Woman Clothed with the Sun — painting by William Blake

National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Comedy of Errors may also be purchased from Main Point Books in Wayne.

Stewart had worked long hours in his bedroom studio to draft dozens of sketches each week which he submitted to Whitney for selection, review and approval by the syndicate before rendering and inking in the final drafts for submission and publication.

From the beginning of his relationship with the syndicate, Stewart had relied heavily on Whitney’s knowledge of the newspaper industry to refine his approach and establish an identity for Kafka. Since Whitney was on the board of editors, and had taken the lead in recommending the series, other members of the board took little notice of the panels Whitney passed along to them at their monthly meetings. The editorial staff of the newspapers in which the cartoons were to be inserted were necessary to the review process, but, in reality, had taken little notice of the panels after the series’ initial release, and provided little or no feedback to Whitney or to Stewart concerning the message, relevance or appropriateness of the content submitted.

Despite the indifference of the editors, by the middle of February Kafka had been viewed by hundreds of thousands of readers, of which fifty had drafted letters to the editors, most of which were ignored and stacked on the corners of desks, unread.

By March, hundreds more letters, postcards and telegrams from readers of the Kafka series had been received, with some finding their way to the “Letters to the Editor” column in papers that had such a section, and ended up being in print.

Some of the comments were positive, including a review by one reader of the Los Angeles Times who wrote: Bravo! Kafka is refreshingly thought-provoking and darkly amusing. My wife and I are eager to follow along on the journey of Mr. Little and see what he’s got planned for us.

Other reviews were not so kind, such as one from a reader of the Chicago Tribune who wrote: I have no idea what the ugly bugs are talking about in your new cartoon, Kafka, and frankly, I really don’t care.

Another letter submitted by a reader of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette wrote: Kafka is on the same page as Miss Peach, a favorite cartoon of mine about a teacher and her students.

The roaches are disturbing to me and to the children I teach, and I urge you to consider removing the series from your comics section... to somewhere else...perhaps the obituary page or the real estate section to accompany ads for low-income housing. It certainly doesn’t belong where it is... or, to my mind, anywhere else in your paper.

The most frequent assessment of the series was echoed by readers nationwide and paraphrased by one critic who read the reviews from several papers: It seems that the Kafka cartoons are meant for a specific audience and are neither funny nor uplifting to most readers, who find them rather disgusting. It seems that the creator must have a message and a market in mind, but if he does, the market seems limited, with my personal thought being who the Hell thought the public needed a comic focused on roaches?

By April, several rural newspapers had made the decision to drop the Kafka series, and replace it with anything else the syndicate had to offer, including the discontinued comic, The Berrys, or 9 to 5, a cartoon that wasn’t particularly humorous, but which also wasn’t offensive.

Whitney shielded Stewart from the brunt of the complaints, as he attempted to guide his cartoonist to embrace more positive themes including skateboarding, space travel, and the exploration of the oceans. Whitney even suggested that Stewart insert more humans into the cartoon and develop narratives that would appeal to children, women, and various ethnicities, even though no one could tell what race the roaches were meant to symbolize.

By June, Stewart was spending a good portion of his day staring at empty sheets of tracing paper, as it was becoming evident that a cartoon featuring cockroaches couldn’t serve to address every issue and please every viewer.

As the negative reviews continued to mount, Whitney knew that he could easily afford to write the series off and take the financial hit, but he was consumed with doubt over his failure to envision the limitations of the cartoon, and saddened by the impact the failure would mean for the future of Stewart.

With the warnings of termination looming, Whitney called Stewart to inform him of the concerns reported to him by the director of the Field Enterprises syndicate, bluntly citing the recent polls and reporting that only 50 newspapers remained committed to the series, and those required a provision that Stewart rework the series to increase its popularity in its markets without providing any clue as to how that could be done.

Stewart listened, but heard little of what Whitney said, realizing that the more he’d modified the cartoon to please the market, the more Kafka suffered from ambiguity and a lack of a clear direction. If he continued on the track he was on and kept adjusting the series to meet everyone’s taste, Stewart knew he would fail, and he had already sunk into a despair that was negatively impacting his creativity and his relationship with Carol, who continued to call, but with whom he avoided contact.

Stewart knew that he couldn’t afford to bail out of his contract, since Whitney had guaranteed him a salary for two years, and he was dependent on Whitney’s funding to salvage whatever he could of his career, if and when the syndicate terminated his contract.

Carol understood the pressure that Stewart was under, and would leave daily messages with his father that she hoped would be passed on, confirming her support for him and encouraging him to call whenever he felt the need to unburden himself of his worries.

As hypocritical as Stewart believed it was for him to pray, he spoke often to the “voice in his head” about his dilemma, and begged for the strength to address and deal with his imminent failure. He blamed no one but himself and his arrogance for his troubles. He knew that Whitney, the syndicate, and the newspapers who supported his cartoon were not responsible for his failure, and that he alone remained in control of his situation, and had to find a suitable solution to the problem.

By July, Stewart’s existing stock of cartoons was nearly depleted, and although he’d heard no further news of a cancellation from Whitney or the syndicate, he was well aware that he alone was responsible for finding a solution to his problem. If he failed to fill the space reserved for the cartoon, he would be in violation of both of his contracts, thus freeing Whitney or Field Enterprises from remuneration for services not rendered.

Just two weeks prior to his 22nd birthday, Stewart awoke from a fitful night of sleep and returned to his drawing board, hoping for inspiration. Without any reason he could later explain, he recalled a book he’d read while at Temple about the 18th century English poet and printmaker William Blake. He remembered how, without much success, he had tried to understand Blake’s poems, and was fascinated with the prints and paintings created by the poet. One such image he recalled was that of a large red dragon with several heads, who descended upon a woman clothed by the sun and wearing a crown with twelve stars, and with the moon under her feet. The painting was supposedly based on a biblical theme, with the dragon embodying Satan, who was exacting revenge on the woman for giving birth to a follower of God. Though somehow connected to Christianity, Blake’s beliefs were constructed from his own imagination. He was self-taught and disregarded many of the rules of art, religion and poetry, and over time became known as an idiosyncratic visionary totally unique to his generation.

Stewart searched through the books in his closet, found the biography he’d read, and scanned its pages, finding the painting that he remembered. He then grabbed his “scrap” of photos of roaches he’d collected over several months. Skipping past the pencil art and picking up his technical pen, he proceeded to humanize the head of the insect, adding tears that flowed from its eyes. He worked down to the thorax and began to draw smaller dead and dismembered roaches in the foreground along with the prothoracic legs that projected past the lower portion of his artwork, defining the panel and revealing the tearful roach carrying an offering of a deceased roach to the reader. Other smaller roaches were then added behind and around the head of the central figure, along with a background stippled by his pen that created various densities of sky and clouds.

Carefully rendered in script between the legs of the roach holding onto the sacrificial roach was the plea, Save us!

Stewart knew that this might be his final published cartoon, but also acknowledged that this panel was completely different from his earlier work that was rendered with an economy of line and brush work. The new panel was densely shaded, which created the illusion that the roach was literally stepping off the page.

Stewart had worked throughout the night with only a bathroom break. The artwork he produced was far more complex than the simple renderings he’d created from rough sketches submitted to Whitney and took far more time to complete in final form.

He knew that this was a breakthrough piece, and one that was like no cartoon he’d seen before. He also knew that the sketch would never be approved by Whitney or the syndicate, and the reality was that he could never maintain the output necessary to submit variations for approval and provide finished drawings this complex for publication.

Stewart packaged up the art and sent it to Whitney along with a note:

This may be my final drawing in the series. It’s not a draft, and not submitted for edits. Hopefully you will approve it for distribution before my series is terminated.

I’ve learned a lot about myself and my work over the past several months, including that I’m not a person well suited to satisfying the wishes of others. I am best when I choose to please myself, and hope that as time goes by, I can move forward in my career, and will be able to find an audience in tune with my voice. I also have learned that until that time arrives, I must find a way to survive using the skills I’ve developed.

I’ve thought about The Cargyls and hope that, at some future date, you or I can use what I’ve learned about people over the past few years to express their varying viewpoints of people as they are, and not who they pretend to be.

I’m afraid that I’ve already become a bit deluded by dreams of wealth and fame, and my failures with Kafka may help me reevaluate the purpose of my life past luxuries that I may desire, but not need.

I greatly appreciate all you’ve done for me, and hope that we can work together in the future.

With fondness and respect,

Stewart

-----------------------------------------

The next morning, Stewart mailed the artwork to Whitney, and then called Carol to apologize to her for not answering her calls.

She told him that she understood, and asked if he was feeling any better.

“I am,” said Stewart. “Much better!”

He then told Carol the story of creating a new style based on a memory of William Blake, and that during the process his burden was lifted as the panel appeared “to draw itself.”

“I had no idea where it was going when I began to ink in the roach — the tears in the insect’s eyes, the bodies draped across its back, and then the offering of the insect beyond the borders of the panel appeared as I stippled them, cut the dots smaller with an X-Acto knife, and watched the drawing evolve.

“I never predicted the panel to be a plea to viewers, until I began penciling in the copy between the roach’s forelegs.”

“I wish I could have seen it before you sent it off,” said Carol.

“Once complete, I looked at it only once,” continued Stewart. “I swear that it came from Blake’s hand rather than from mine, but I know that that’s a fantasy.”

“Do you think you can do another like it?” asked Carol, having no idea of the process, or the time it might take.

“I believe I can,” answered Stewart, “but I know I can’t return to creating cartoons based on someone else’s directions. So I may never be able to afford the home in Manhasset that you wouldn’t want to live in. I think this was a wake-up call to have me reevaluate my goals as well as to explore my assets realistically.”

“I appreciate your understanding of who I am,” responded Carol, “but I’ve also been considering my statement on my inflexibility in maintaining my narrow viewpoint of the world. Hopefully at some time in the future, our worlds might have a chance to merge.”

“I sure hope so, Carol. But I’m in no hurry now, since I may be living with my parents for much longer than I had intended.”

“I believe in you, Stewart. You’ll figure it out. And it will be fascinating to see how you address each stage in the process.”

“I’ve never said it to you before, Carol, but I do love you.”

“And I love you, Stewart. But from what I’ve learned about love, it can come and go, and requires a lifetime of work for two people to maintain it.

“We’ve only been together a short while, and from what I already know about myself, I believe that Andy and I would probably not have been able to hold on to our love for even as long as you and I have been together.

“That being said, give me a call after you hear from Whitney, and then, if all goes well, let’s schedule a date. It seems that my body misses you — at least as much as my heart.”

----------------------------------------

Comments

Post a Comment